Could Zika Be The Next HIV?

08/15/2016 11:56AM | 7843 views“Laurie Garrett is a Senior Fellow for Global Health at the Council on Foreign Relations, and a Pulitzer Prize-winning writer. The opinions expressed in this commentary are hers.”

(CNN)Thirty-five years ago, alert physicians in the United States spotted a new disease, caused by a virus that had been in circulation, unnoticed, for decades in people, and millennia in monkeys.

The virus had hit pay dirt, racing through the gay sexual revolution where one man might have sex with 30 other men a year, giving the virus exponential rates of infection.

Over time, the virus' transmission shifted, especially in Africa, from rare cases of monkey-to-human transmission to general heterosexual spread, with women today five times more likely to be newly infected compared to men, thanks to sexual cultures that favor male promiscuity.

That was HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, which currently infects more than 37 million people living all over the world.

A key lesson of AIDS is that a virus—in HIV's case, infecting African monkeys—might pass rarely, but repeatedly, to human beings for decades before arriving in a context of epidemic potential.

Adapting to new modes of transmission and targeting novel species, the microbe can exist for thousands of years before beginning to achieve previously unimaginable feats, with devastating impact.

Now the world is facing a virus that seems poised to make a similar leap: the Zika virus.

Like HIV, Zika originated in central Africa, very rarely infecting human beings, and circulating among rainforest primates. Unlike HIV, Zika had the ability to fly, carried by Aedes aegypti mosquitoes from one monkey or human, to another.

Since reaching Brazil in 2013, where it has spread explosively over the last 12 months, Zika has demonstrated capabilities not seen, or extremely rarely noted, with any other insect-carried microbes.

Most worrying, Zika has shed its mosquito transport dependency, becoming an efficient resident of human semen, and spread from male-to-female (and male-to-male) via sexual intercourse.

This week researchers reported finding Zika in a woman's vagina, noting that, "the very presence in the female genital tract [implies] that sexual transmission from women to men could occur." And barely had the ink dried on that report when the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention announced today that a woman who traveled in a Zika-hit country, who got infected through a mosquito bite, has passed the virus onto her male sexual partner in New York City, marking the first documented case of female to male sexual transmission in the U.S. (and the 14th documented sexual transmission in the U.S. overall).

If Zika finds its way into an especially sexually active community, it could well become a threat not only in America's southern, mosquito-infested states, but anywhere in the world.

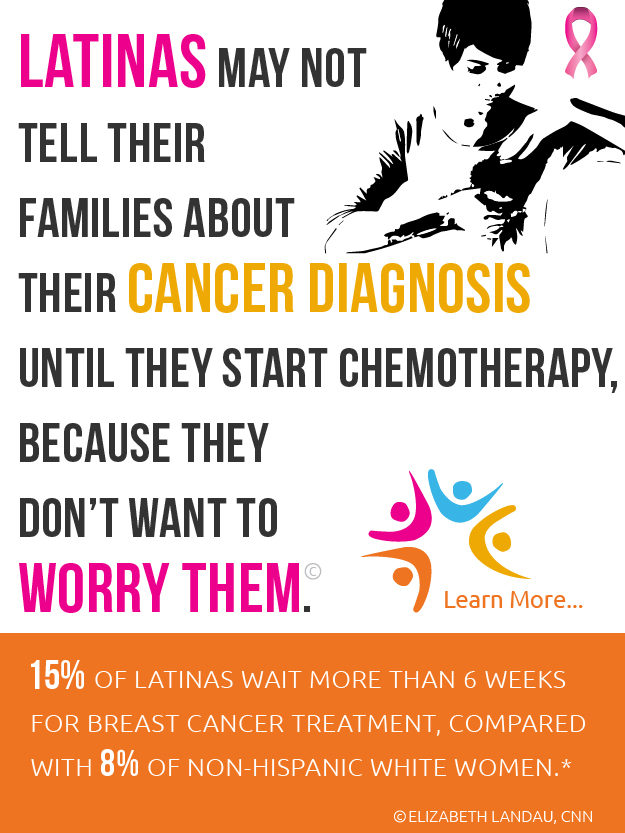

Like HIV, the Zika virus would likely find its way into populations that feel discriminated against by the general population, and take its toll disproportionately among teenage girls and young women.

And while politicians play partisan games with funding on Capitol Hill, government and philanthropic donors ignore the World Health Organization's pleas for a measly $122 million to fight it, and state health agencies scramble to find anti-mosquito resources, the virus is spreading in new ways, causing an ever-widening range of dangerous birth defects and human illnesses.

"I am concerned that the goose is cooked. This funding is done. It's not coming to us," Dr. Umair Shah, a public health official in Harris Country, Texas told NBC News. "We cannot spray our way out of this situation," Shah added, saying pesticides won't be enough to stop Zika at this late date in the American South.

Post your Comment

Please login or sign up to comment

Comments