Black and Hispanic Americans turn to doctors who look like them for reassurance on vaccinations.

01/19/2021 06:00AM | 2450 viewsBy Gina Kolata

Denese Rankin, a 55-year-old retired bookkeeper and receptionist in Castleberry, Ala., did not want the Covid-19 vaccine. Her opinion toward the vaccine was like many Black, rural Americans: The vaccine had come about too quickly to be safe.

Her worry prompted her niece, Dr. Zanthia Wiley, to come to town. Dr. Wiley, who is an infectious disease specialist at Emory University in Atlanta, said one of her goals on her trip was to let her family hear the truth about vaccines from someone they knew, someone who is Black.

Across the country, Black and Hispanic physicians like Dr. Wiley are reaching out to Americans in minority communities who are suspicious of Covid-19 vaccines and often mistrustful of the officials they see on television telling them to get vaccinated. Many are dismissive of public service announcements, the doctors say, and of the federal government. The government’s long history of medical experimentation on Black people is also not helping the matter.

But it’s the assurance from Black and Hispanic doctors that can make all the difference.

“I don’t want us to benefit the least,” Dr. Wiley said. “We should be first in line to get it.”

Physicians across the U.S. are making themselves readily available to dispel myths and address concerns about Covid-19 vaccinations. Some have even gone as far to host video calls and post messages on social media.

“I think it makes a whole lot of difference,” said Dr. Valeria Daniela Lucio Cantos, an infectious disease specialist at Emory who has been running online town halls and webinars on the subject of vaccination.

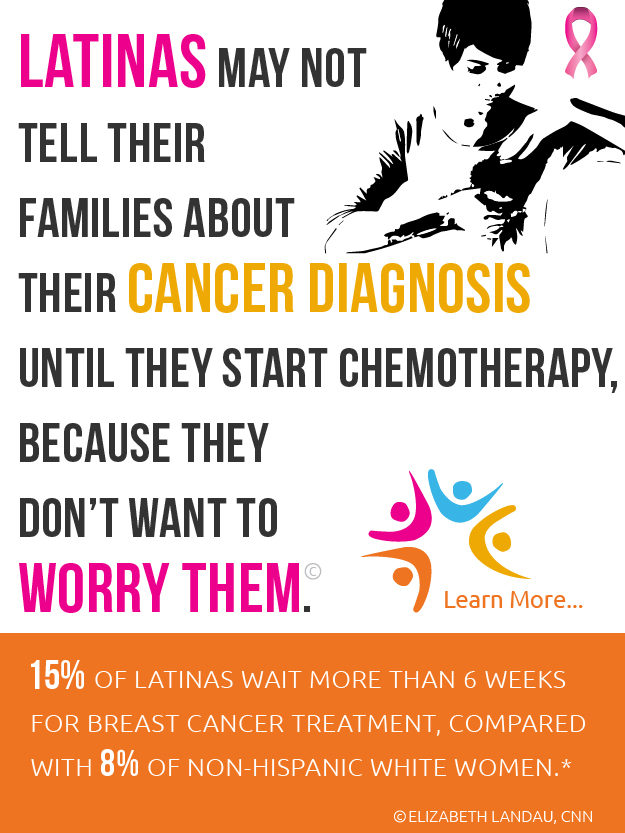

Black and Hispanic communities have been disproportionately affected by the coronavirus, with Black and Hispanic Americans being three times more likely to be infected with the coronavirus compared to white people.

Many of the vaccine-hesitant are linchpins of health in their own families. Ms. Rankin, for example, helps care for Dr. Wiley’s grandmother, who is blind, and her grandfather, who cannot walk. Ms. Rankin looks in on Dr. Wiley’s mother, whose health is fragile. And she is the single mother of three girls, including a 14-year-old who still lives at home.

“If my aunt got infected, my family would be in tough shape,” Dr. Wiley said.

Dr. Virginia Banks, an infectious disease specialist in Youngstown, Ohio, who is Black, said she has seen too many people — and not all of them old — suffer and die in the pandemic. She often recites stories of her experiences dealing with those infected to people hesitant about getting vaccinated.

Post your Comment

Please login or sign up to comment

Comments