Junk Food Ads Disproportionately Target Black and Hispanic Kids, Study Finds

03/26/2019 06:00AM | 8633 viewsResearchers find a growing disparity between ads targeted to white teens and those aimed at minority youth.

A report released on Tuesday finds that junk food advertising continues to disproportionately target black and Hispanic youth, contributing to health disparities.

From 2013 to 2017, spending on TV advertising for restaurants, food and beverages decreased by 4 percent overall, the researchers found, while spending for programs directed at black teens increased by 50 percent — from $217 million to $333 million — underlining the disparity in exposure to advertising between white and black youth.

The report also found that Hispanic children and teens viewed on average 2 more Spanish-language food ads, in addition to English-language TV ads in 2017.

“Food companies hardly ever market fruit and vegetables, water or healthy juices,” said Jennifer Harris, a lead author of the study and director of marketing initiatives for the Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity at the University of Connecticut. “The money put towards such advertisements is less than 3 percent for the general population and less than 1 percent to blacks and Hispanics.”

Researchers from the University of Connecticut, Drexel University and the University of Texas Health Science Center looked at 32 restaurants and food and beverage companies that spent over $100 million each on total TV advertising in 2017.

In total, the food companies spent $11 billion on advertising that year, with 80 percent spent on ads for fast food, candy, sugary drinks and unhealthy snacks.

McDonald’s, Subway, Wendy’s, and Taco Bell ranked at the top for targeted advertising spending on Spanish-language TV; and Taco Bell, Domino’s, Burger King, Wendy’s, and Arby’s ranked at the top in targeted advertising spending on Black-targeted TV, in part, due to higher total advertising budgets.

“At best, these advertising patterns imply that food companies view black consumers as interested in candy, sugary drinks, fast food and snacks with a lot of salt, fat or sugar, but not in healthier foods,” said Shiriki Kumanyika, a study co-author and chair of the Council on Black Health at Drexel.

“The marketing is so pervasive that it’s almost invisible,” Kumanyika told NBC News. “I’m not sure it’s really widely known in black communities that this amount of money is being used to promote unhealthy products. Some companies spend quite a bit of money to endear themselves to these communities that they don’t even give public health organizations a chance.”

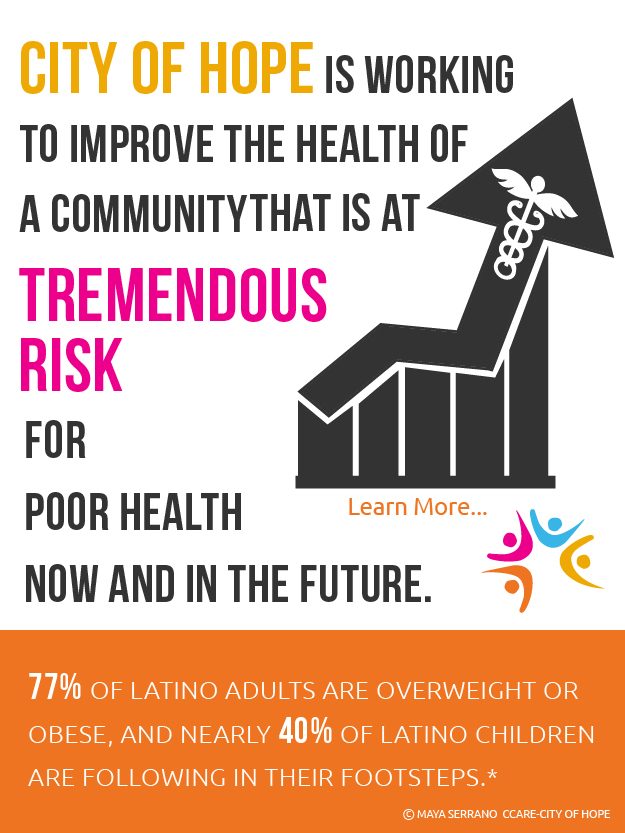

Another factor that contributes to poor nutrition among some minorities is poverty. Studies that compare communities with similar poverty rates have found that black and Hispanic neighborhoods tend to have fewer large supermarkets and more small grocery stores than white neighborhoods do. These stores offer fewer of the healthy alternatives like whole-grain foods, dairy products and fresh fruits and vegetables that a supermarket would provide.

Further compounding this problem is the prevalence of food deserts — areas in which residents are hard-pressed to find affordable, healthy food.

The government defines a food desert as an area where 33 percent of a city’s residents live more than one mile from a supermarket and 20 percent earn salaries below the poverty line. Many residents of food deserts — which are disproportionately located in communities of color — do not have cars and lack access to public transportation, making it difficult to get to a grocery store.

The marketing is so pervasive that it’s almost invisible.

Fast food and unhealthy food options that are marketed as cheaper and more easily accessible in small stores become more desirable. As a result, the obesity rates in these areas are generally higher, meaning life-threatening illnesses like diabetes and heart disease are on the rise.

Junk food — any food that is highly processed, high in calories and low in nutrients — is usually high in added sugars, salt and saturated or trans fats. Some evidence suggests that junk food is as addictive as alcohol and drugs, leading health policy activists to call for food justice.

“Food and beverage companies have to stop taking advantage of our kids,” Kumanyika said. "They inadvertently contribute to poor health in black communities by heavily promoting products linked to an increased risk of obesity, diabetes and high blood pressure.”

Dr. Shamard Charles is a physician-journalist for NBC News and Today, reporting on health policy, public health initiatives, diversity in medicine, and new developments in health care research and medical treatments.

Post your Comment

Please login or sign up to comment

Comments