Q&A with Dr. Jeffrey Weitzel: Research Addresses Genetic Mutations and Disparities in Latina Breast Care (Part 1)

02/01/2015 11:37AM | 7957 viewsBy Breast Cancer Research Foundation

Dr. Jeffery Weitzel is Division Chief of Clinical Cancer Genetics at City of Hope in California as well as a Breast Cancer Research Foundation (BCRF) grantee since 2013. At City of Hope, Dr. Weitzel leads a clinical, research and training program that emphasizes translational research in genomic cancer risk assessment, chemoprevention, targeted therapy, clinical and psychosocial outcomes, genetic epidemiology and health services in underserved minorities. For over a decade, he has been interested in hereditary cancer in Latin America with the aim of increasing awareness of inherited risk and access to screening and prevention. As part of its partnership with Healthy Hispanic Living, BCRF recently spoke with Dr. Weitzel about his work in the Latina community, both in the U.S. and Latin America, and asked for his insight on new discoveries that are helping us to understand the role of genetics in breast cancer risk for Hispanic women.

What is the landscape of breast cancer in Latinas? How do the incidence and mortality rates differ from non-Hispanic whites or other minority populations?

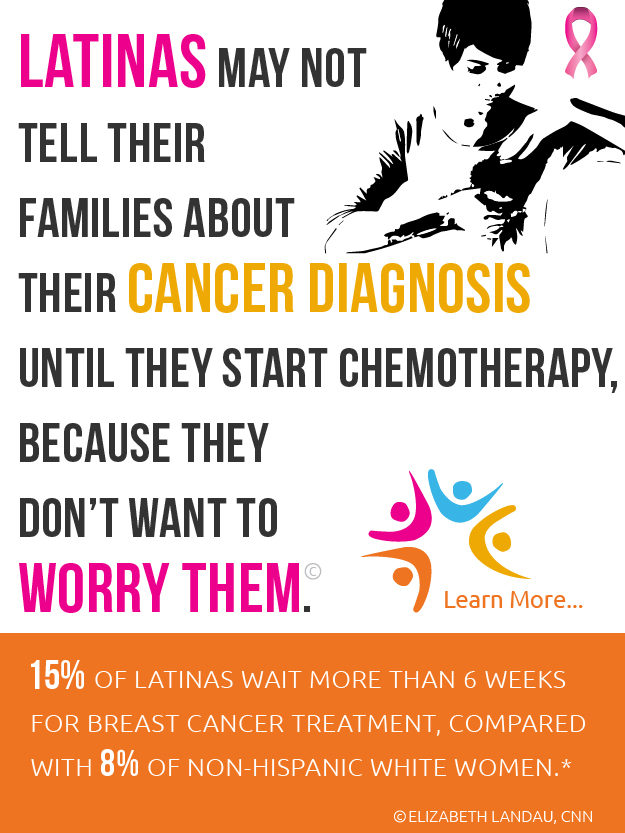

JW: It's well recognized that Latinas have a lower incidence of breast cancer compared to non-Hispanic whites. In spite of that, they are more likely to be diagnosed with advanced breast cancers and are more likely to die of their disease than the general population.

What do we know about role of genetics in breast cancer risk in Latinas?

JW: Because Latinas are disproportionately underrepresented in research and disproportionately economically disadvantaged and uninsured, there is relatively little information about the spectrum of genetic mutations seen in this population. Currently, we only have information on the BRCA genes. Nobody as yet has looked at mutations in other breast cancer risk genes in the Latina population, but our group has started to do so. For example, we have identified several mutations in PALB2, a gene that was recently characterized as an intermediate breast cancer risk gene.

How did you come to be interested in breast cancer disparities in Latina populations?

JW: Much of it has to do with taking care of the folks in our community. As you know, I'm a medical oncologist and geneticist in Los Angeles. Around 2000, Dr. Nancy Feldman, a friend and colleague from the Olive View-UCLA Medical Center County hospital, which serves a predominantly Latino population, told me about the number of young Latinas coming in with advanced breast cancer. At that time Medicaid was not providing any coverage for genetic testing, so even those women with a family history of the disease were not getting genetic screening.

Our group helped to develop the science that integrates genetics into the care of women. Those studies defined the medical necessity and the need to know, especially with reference to mutations in the BRCA genes, the most commonly mutated genes in hereditary breast cancer in any population. Learning about the lack of screening in a high-risk population drove us to focus our attention on young Latinas with breast cancer.

How did your genetic screening program come about?

JW: First, we surveyed the underserved and uninsured Latina community we had access to through Olive View to learn their attitudes about prevention and understanding of genetics and cancer. Our surveys revealed that 80 percent of the patients would be receptive to genetic testing and counseling.

Based on the survey, we decided to test the uptake of genetic counseling and testing in an outreach project at the hospital. In other words: if we build it [a genetic counseling and testing program], will they come? We provided trained genetic counselors and secured funding to pay for genetic testing for those with family histories. And they came. We had an 80 percent response rate, which is even better than what we see in our insured patients.

The next step was to determine whether the counseling and testing had the desired impact. We wanted to know if they came [to the clinic], did they learn and, if they learned, did they do the right thing. We conducted a series of pre- and post-tests and showed that participants learned about cancer genetics. We were then able to document that those who tested positive for the BRCA1/2 mutation shared that risk information with their families so that prevention measures could be taken.

These studies represent a decade of progressive health services research, combining elements of behavioral and social sciences and genetic epidemiology. Health services research is the critical last step in translational research and funding is very hard to get. It really takes the most prescient agencies, like BCRF, to have the vision and see why these studies need to be done. We are incredibly grateful for the support we've received from BCRF to continue to build on our earlier work

What have been some of the most important findings from these genetic screening studies?

JW: One of the main things we learned was that there were certain repeating mutations in the Latina patients, similar to what we see in the Jewish population. Five mutations accounted for over 50 percent of the positive cases in our screening studies. That discovery made us think about the ancestry of these patients. As Mexican descendants, they shared ancestry with the indigenous people of Mexico, Europeans representing Spanish colonization, and Africans reflecting the slave trade. We studied anthropology and did haplotyping experiments and discovered that most of the recurring mutations could be traced back to Spain (likely coincident with Spanish colonization ~500 years ago), demonstrating the influence of world history on inherited risk of disease in distinct populations. This is likely due to the fact that these were agrarian people who didn't migrate, therefore showing us that certain genetic patterns are traceable to geographic areas.

We also found some mutations in clusters from unrelated families specific for Guatemala or El Salvador, for example. We found the same BRCA1 mutation, 185delAG, which was previously believed to be specific to Ashkenazi Jews. This tells us that this mutation was present among Sephardic Jews and likely predates the separation of the Ashkenazi population, probably dating back to the second Jewish Diaspora, which occurred around 70 BCE.

Breast cancer incidence is lower in Latinas than in non-Latina whites but Latinas tend to get breast cancer at a young age and more often have more aggressive types, such as Triple Negative Breast cancer (TBNC). What can your work tell us about these findings?

JW: Our work has revealed that while the overall risk of breast cancer is lower in Latinas, the likelihood that an early onset breast cancer or a diagnosis of triple negative breast cancer is due to inherited predisposition is as high or higher in this group of women than any other population. Therefore, there is an enormous opportunity—as well as responsibility—to provide appropriate genetic counseling and screening to prevent breast cancer.

This discussion will continue in Part 2 of the Q&A between BCRF and Dr. Weitzel.

Post your Comment

Please login or sign up to comment

Comments